Custom Search

|

|

?

Rabies virus |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus classification | ||||||||||

|

| ICD-10 | A82 |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 071 |

Rabies (from a Latin word meaning rage) is a viral disease that causes acute encephalitis in animals and people. It can affect most species of warm-blooded animals, but is rare among non-carnivores. In unvaccinated humans, rabies is almost invariably fatal once full-blown symptoms have developed, but post-exposure vaccination can prevent symptoms from developing.

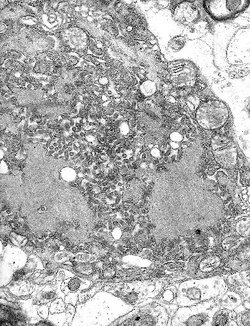

Micrograph with numerous rabies viruses (small dark-grey rod-like particles) and

Negri bodies, larger cellular inclusions typical of Rabies infection

Micrograph with numerous rabies viruses (small dark-grey rod-like particles) and

Negri bodies, larger cellular inclusions typical of Rabies infection

The stereotypical image of an infected ( rabid ) animal is a mad dog foaming at the mouth, but cats, ferrets, raccoons, skunks, fox, coyotes and bats also become rabid. Squirrels, chipmunks, other rodents and rabbits are very seldom infected, perhaps because they would not usually survive an attack by a rabid animal. Rabies may also be present in a so-called 'paralytic' form, rendering the infected animal unnaturally quiet and withdrawn.

The virus is usually present in the saliva of a symptomatic rabid animal; the route of infection is nearly always by a bite. By causing the infected animal to be exceptionally aggressive, the virus ensures its transmission to the next host. Transmission has occurred via an aerosol through mucous membranes; transmission in this form may have happened in people exploring caves populated by rabid bats. Transmission from person to person is extremely rare, though it can happen through transplant surgery (see below for recent cases), or even more rarely through bites or kisses.

After a typical human infection by animal bite, the virus directly or indirectly enters the peripheral nervous system. It then travels along the nerves towards the central nervous system. During this phase, the virus cannot be easily detected within the host, and vaccination may still confer cell-mediated immunity to pre-empt symptomatic rabies. Once the virus reaches the brain, it rapidly causes an encephalitis and symptoms appear. It may also inflame the spinal cord producing myelitis.

The period between infection and the first flu-like symptoms is normally 3-12 weeks, but can be as long as two years. Soon after, the symptoms expand to cerebral dysfunction, anxiety, insomnia, confusion, agitation, abnormal behaviour, hallucinations, progressing to delirium. The production of large quantities of saliva and tears coupled with an inability to speak or swallow are typical during the later stages of the disease; this is known as hydrophobia . Death almost invariably results 2-10 days after the first symptoms; the handful of people who are known to have survived the disease were all left with severe brain damage, with the recent exception of Jeanna Giese (see below).

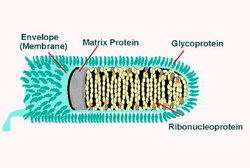

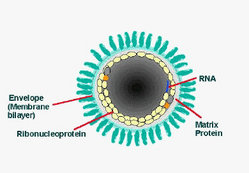

The Rabies virus is a Lyssavirus. This genus of RNA viruses also includes the Aravan virus, Australian bat lyssavirus, Duvenhage virus, European bat lyssavirus 1, European bat lyssavirus 2, Irkut virus, Khujand virus, Lagos bat virus, Mokola virus and West Caucasian bat virus. Lyssaviruses have helical symmetry, so their infectious particles are approximately cylindrical in shape. This is typical of plant-infecting viruses; human-infecting viruses more commonly have cubic symmetry and take shapes approximating regular polyhedra.

The Lyssaviruses are the only viruses known to travel along the nerves after infection. Biopsy shows typical Negri bodies in the infected neurons.

The Rabies virus has a bullet-like shape with a length of about 180 nm and a cross-sectional diameter of about 75 nm. One end is rounded or conical and the other end is planar or concave. The lipoprotein envelope carries knob like spikes, composed of Glycoprotein G. Spikes do not cover the planar end of the virion. Beneath the envelope is the membrane or matrix (M) protein layer which may be invaginated at the planar end. The core of the Virion consists of helically arranged ribonucleoprotein. The genome is unsegmented linear negative sense RNA. Also present in the nucleocapsid are RNA dependent RNA transcriptase and some structural proteins.

There is no known cure for symptomatic rabies, but it can be prevented by vaccination, both in humans and other animals. Virtually every infection with rabies was historically a death sentence, until Louis Pasteur developed the first rabies vaccination in 1886. Pasteur demonstrated its effectiveness by treating Joseph Meister, who had been bitten by a rabid dog.

Pasteur's vaccine consisted of a sample of the virus harvested from infected (and necessarily dead) rabbits, which was weakened by allowing it to dry. Similar nerve tissue-derived vaccines are still used today in developing countries, and while they are much cheaper than modern cell-culture vaccines, they are not as effective and carry a certain risk of neurological complications.

The human diploid cell rabies vaccine (HDCV) was started in 1967. Human diploid cell rabies vaccines are made using the attenuated Pitman-Moore L503 strain of the virus. Human diploid cell rabies vaccines have been given to more than 1.5 million people worldwide as of 2006. Newer and less expensive purified chick embryo cell vaccine, and purified Vero cell rabies vaccine are now available. The purified Vero cell rabies vaccine uses the attenuated Wistar strain of the rabies virus, and uses the Vero cell line as its host.

Treatment after exposure (known as post-exposure prophylaxis or PEP ) is highly successful in preventing the disease if administered promptly, within 14 days after infection. In the United States, the treatment consists of a regimen of one dose of immunoglobulin and five doses of rabies vaccine over a 28-day period. Rabies immunoglobulin and the first dose of rabies vaccine should be given as soon as possible after exposure, with additional doses on days 3, 7, 14, and 28 after the first. The vaccinations are relatively painless and are given in one's arm, in contrast to previous treatments which were given through a large needle inserted into the abdomen. In case of animal bites it is also helpful to remove, by thorough washing, as much infectious material as soon as possible. Since the development of effective human vaccines and immunoglobulin treatments the US, death rate from rabies has dropped from 100 or more annually in the early 20th century, to 1-2 per year, mostly caused by bat bites, which may go unnoticed by the victim and hence untreated.

PEP is effective in treating rabies because the virus must travel from the site of infection through the peripheral nervous system (nerves in the body) before infecting the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and glands to cause lethal damage. This travel along the nerves is usually slow enough that vaccine and immunoglobulin can be administered to protect the brain and glands from infection. The amount of time this travel requires is dependent on how far the infected area is from the brain: if the victim is bitten in the face, for example, the time between initial infection and infection of the brain is very short and PEP may not be successful.

Currently pre-exposure immunization has been in domesticated and wild animal populations. In the United States domestic dogs are required to be vaccinated. A new, orally active, genetically recombined virus vaccine for raccoon rabies awaits licensing by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as of 2006. A gene that produces a protein in the rabies virus outer coat was inserted into a live vaccinia virus using recombinant DNA technology. When the modified vaccinia virus infects a wild animal, it produces the antigenic protein normally made by the rabies virus. The wild animal's body recognizes the protein as foreign, and the animal develops active immunity. The plan for immunization of wild populations involves dropping bait containing food wrapped around a small dose of the live virus. The bait would be dropped by helicopter concentrating on areas that have not been infected yet.

More than 99% of all human deaths from rabies occur in Africa, Asia and South America; India alone reports 30,000 deaths annually. [1]

Dog licensing, killing of stray dogs, muzzling and other measures contributed to the eradication of rabies from Great Britain in the early 20th century. More recently, large-scale vaccination of cats, dogs and ferrets has been successful in combatting rabies in some developed countries.

A rabid dog, with saliva dropping out of the mouth

A rabid dog, with saliva dropping out of the mouth

Rabies virus survives in widespread, varied, rural wildlife reservoirs. However, in Asia, parts of Latin America and large parts of Africa, dogs remain the principal host. Mandatory vaccination of animals is less effective in rural areas. Especially in developing countries, animals may not be privately owned and their destruction may be unacceptable. Oral vaccines can be safely distributed in baits, and this has successfully impacted rabies in rural areas of France, Ontario, Texas, Florida and elsewhere. Vaccination campaigns may be expensive, and a cost-benefit analysis can lead those responsible to opt for policies of containment rather than elimination of the disease.

Rabies was once rare in the United States outside the Southern states, but raccoons in the mid-Atlantic and northeast United States have been suffering from a rabies epidemic since the 1970s, which is now moving westwards into Ohio. [2] The particular variant of the virus has been identified in the southeastern United States raccoon population since the 1950s, and is believed to have traveled to the northeast as the result of infected raccoons being among those caught and transported from the southeast to the northeast by hunters attempting to replenish the declining northeast raccoon population (Nettles VF, Shaddock JH, Sikes RK, Reyes CR. Rabies in translocated raccoons . Am J Public Health 1979;69:601-2.). As a result, urban residents of these areas have become more wary of the large but normally unseen urban raccoon population. It has become the common assumption that any raccoon seen in daylight is infected; certainly the reported behavior of most such animals appears to show some sort of illness, and autopsies usually confirm rabies. Whether as a result of increased vigilance or just the normal avoidance reaction to any animal not seen in the course of day to day life, such as a raccoon, there have been no documented human rabies cases as a result of this variant. This does not include, however, the greatly increasing rate of prophylactic rabies treatments in cases of possible exposure, which numbered less than 100 persons annually in New York State before 1990, for instance, but rose to approximately 10,000 annually between 1990 and 1995. At approximately $1500 per course of treatment, this represents a considerable public health expenditure. Raccoons do constitute approximately 50% of the approximately 8,000 documented animal rabies cases in the United States (Krebs JW, Strine TW, Smith JS, Noah DL, Rupprecht CE, Childs JE. Rabies surveillance in the United States during 1995 . J Am Vet Med Assoc 1996;204:2031-44). Domestic animals constitute only 8% of rabies cases (ibid.), but are increasing at a rapid rate.

In the midwestern United States, skunks are the primary carriers of rabies, comprising 144 of the 237 documented animal cases in 1996. The most widely distributed reservoir of rabies in the United States, however, and the source of most human cases in the U.S., are bats. Nineteen of the 22 human rabies cases documented in the United States between 1980 and 1997 have been identified genetically as bat rabies. In many cases, victims are not even aware of having been bitten by a bat, assuming that a small puncture wound found after the fact was the bite of an insect or spider; in some cases, no wound at all can be found, leading to the hypothesis that in some cases the virus can be contracted via inhaling airborne aerosols from the vicinity of a bat or bats. For instance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned on May 9, 1997, that a woman who died in October, 1996 in Cumberland County, Kentucky and a man who died in December, 1996 in Missoula County, Montana were both infected with a rabies strain found in silver-haired bats; although bats were found living in the chimney of the woman's home and near the man's place of employment, neither victim could remember having had any contact with them. This inability to recognize a potential infection, in contrast to a bite from a dog or raccoon, leads to a lack of proper prophylactic treatment, and is the cause of the high mortality rate for bat bites.

In case of an attack by a possibly rabid animal, most states in the United States allow the killing of the attacking animal. Because a rabies diagnosis requires that the brain tissue be preserved, it is recommended that rabid animals are not to be shot in the head.

Australia is one of the few parts of the world where rabies has never been introduced. However, the Australian Bat Lyssavirus occurs naturally in both insectivorous and fruit eating bats (flying foxes) from most mainland states. Scientists believe it is present in bat populations throughout the range of flying foxes in Australia.

Many territories, such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, Hawaii, and Guam, are free of rabies (although there may be a very low prevalence of rabies among bats in the UK; see below).

Several recently publicised cases have stemmed from bats, which are known to be a vector for rabies.

The United Kingdom, which has stringent regulations on the importation of animals, had also been believed to be entirely free from rabies until 1996 when a single Daubenton's bat was found to be infected with a rabies-like virus usually found only in bats - European Bat Lyssavirus 2 (EBL2). There were no more known cases in the British Isles until September 2002 when another Daubenton's bat tested positive for EBL2 in Lancashire. A bat conservationist who was bitten by the infected bat received post-exposure treatment and did not develop rabies.

Then in November 2002 David McRae, a Scottish bat conservationist from Guthrie, Angus who was believed to have been bitten by a bat, became the first person to contract rabies in the United Kingdom since 1902. He died from the disease on November 24, 2002.

In October 2004 a wild female brown bear killed one person and injured several others near the city of Brasov, Central Romania. The bear was killed by hunters and diagnosed with rabies. More than one hundred people were vaccinated afterwards.

In November 2004, Jeanna Giese, a 15-year old girl from Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, became one of only six people known to have survived rabies after the onset of symptoms, and the first known instance of a person surviving rabies without vaccine treatment. All of the other five received vaccination before symptoms developed. Giese's disease was already too far progressed for the vaccine to help, and she was considered too weak to tolerate it. Doctors at the Children's Hospital of Wisconsin in Wauwatosa, a suburb of Milwaukee, achieved her survival with an experimental treatment that involved putting the girl into a drug-induced coma, and administering a cocktail of antiviral drugs. Giese had symptoms of full-blown rabies when she sought medical help, 37 days after being bitten by a bat. Her family did not seek treatment at the time because the bat seemed healthy. Jeanna regained her weight, strength, and coordination while in the hospital. She was released from the Children's Hospital of Wisconsin on January 1, 2005.

Rabies is known to have been transmitted between humans by transplant surgery. The medical advisory web site Manbir Online notes Under no circumstances should a cornea be transplanted from a donor, who died of an undiagnosed neurological disorder.

Infections by corneal transplant have been reported in Thailand (2 cases), India (2 cases), Iran (2 cases), the United States (1 case), and France (1 case). The CDC documents the case in France in 1980. Details of two further cases of infection resulting from corneal transplants were described in 1996.

In June 2004, three organ recipients died in the United States from rabies transmitted in the transplanted kidneys and liver of an infected donor from Texarkana. There are bats near the donor's home, but he did not mention having been bitten. The donor is now reported to have died of a cerebral hemorrhage, the culmination of an unidentified neurological disorder, although recipients are said to have been told the cause of death had been a car crash. Marijuana and cocaine were found in the donor's urine at the time of his death, according to a report in The New England Journal of Medicine. The surgeons

thought he had suffered a fatal crack-cocaine overdose, which can produce symptoms similar to those of rabies. 'We had an explanation for his condition,' says Dr. Goran Klintmalm, a surgeon who oversees transplantation at Baylor University Medical Center, where the transplants occurred. 'He'd recently smoked crack cocaine. He'd hemorrhaged around the brain. He'd died. That was all we needed to know.' ... Because of doctor-patient confidentiality rules, doctors involved with this case would not talk about it on the record, but a few did say that no cocaine was found in the donor's blood, the E.R. doctors might have investigated his symptoms more aggressively instead of assuming he had overdosed. (Because no autopsy was done, doctors have not been able to establish whether the rabies or the drugs actually killed him.) (The New York Times Magazine, July 10, 2005)

In February 2005, three German patients in Mainz and Heidelberg were diagnosed with rabies after receiving various organs and cornea transplants from a female donor. Two of the infected people died. Three other patients who received organs from the woman have not yet shown rabies symptoms. The 26 year old donor had died of heart failure in December 2004 after consuming cocaine and ecstasy. In October 2004, she had visited India, one of the countries worst affected by rabies world-wide. Dozens of medical staff were vaccinated against rabies in the two hospitals as a precautionary measure.

Associated Press reports that Donated organs are never tested for rabies. The strain detected in the victims' bodies is one commonly found in bats, health officials said. According to CNN Rabies tests are not routine donor screening tests, Virginia McBride, public health organ donation specialist with the Health Resources and Services Administration, said. The number of tests is limited because doctors have only about six hours from the time a patient is declared brain-dead until the transplantation must begin for the organs to maintain viability.

Rabies is endemic to many parts of the world, and one of the reasons given for quarantine periods in international animal transport has been to try to keep the disease out of uninfected regions. However, most developed countries, pioneered by Sweden, now allow unencumbered travel between their territories for pet animals that have demonstrated an adequate immune response to rabies vaccination.

Such countries may limit movement to animals from countries where rabies is considered to be under control in pet animals. There are various lists of such countries. The United Kingdom has developed a list, and France has a rather different list, said to be based on a list of the Office International des Epizooties (OIE). The European Union has a harmonised list. No list of rabies-free countries is readily available from OIE.

However, the recent spread of rabies in the northeastern United States and further may cause a restrengthening of precautions against movement of possibly rabid animals between countries.

Since there is no USDA-approved vaccine or quarantine period for skunks, pet skunks are frequently put down after biting a human.

The post-exposure rabies series must be administered to the bite victim before the disease progresses too far. For that reason, there has to be a means of determining whether the animal has rabies within a reasonable amount of time. Without a recognized quarantine period for skunks, there is no way of knowing how long to watch the animal for signs of the disease. That leaves no option but to kill the skunk and test its brain cells for rabies.

Owners have recently organized to campaign for USDA approval of a vaccine and quarantine period for skunks in the United States.